2830/2850 Lansdowne Road

This proposed development involves two adjacent lots in the Uplands on Lansdowne Road, located on the north side between Ripon Road and Norfolk Road. Both properties are zoned R-2 Residential Use. The purpose of the application is to permit the proposed construction of a Small Scale Multi Unit Housing development consisting of three homes on each of the two subject properties (two principal buildings and one Accessory Dwelling Unit/per lot), for a total of six residences across the two lots, accessed by a single shared driveway in the middle of the two lots.

At its July 14/’25 presentation to the Advisory Design Panel on Uplands Design and Siting (ADP), Oak Bay planning staff described the development as “six units each having a unique design in a similar style which creates architecturally harmonious appearance”. The individual units would each have their own yard areas demarcated by fences and will appear as six individual homes on a shared driveway. The proposed development is intended to add diversity to the high-quality housing stock in Uplands by offering modern dwelling units with smaller and lower-maintenance yards that are still designed to be in keeping with the elevated architectural character of the neighbourhood.

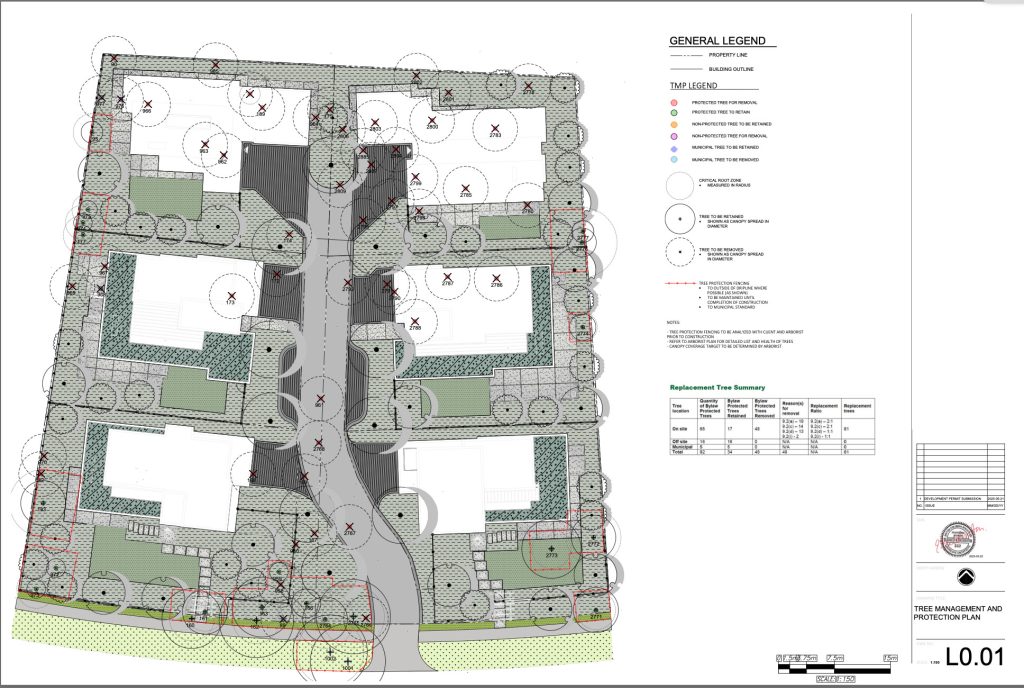

At the present time it is not known whether the planting plan will meet the 45% canopy coverage target required for R2 zoned properties under the Tree Protection bylaw. OB staff has stated that “given the volume of trees to be replanted, it seems very likely the target will be met or exceeded.

Letter from the Garry Oak Meadow Preservation Society

The proposed development at 2830–2850 Lansdowne Road, in its current form with six (6) buildings, exceeds the site’s ecological capacity. As designed, it places significant pressure on surrounding

Garry oak and associated ecosystems, and may compromise the long-term health of Oak Bay’s native urban forest. We are concerned this sets a precedent that prioritizes minimal short-term gains over government commitments to support a National Historic Site, climate resilience, biodiversity, and the integrity of this rare habitat. The loss of canopy, habitat, and ecosystem services far outweighs the gains.

For these reasons, we respectfully urge Council to choose Option #2: Deny the Uplands Siting and Design application (ADP00192). At a minimum, we ask that Council require the removal of the Accessory Dwelling Units, limit this project to the proposed four (4) primary housing units, and ensure the preservation of the Garry oaks that would otherwise be removed under the current design. Council’s decision today will shape access to nature and the health of this urban forest for generations.

The District of Oak Bay, along with the Governments of BC and Canada, have obligations to uphold their commitments to climate resilience, biodiversity, and cultural heritage:

Garry oak ecosystems are Indigenous food systems. The Lək̓ʷəŋən peoples have stewarded kwetlal (camas) and associated ecosystems in the Uplands area for millennia. Respecting these traditions supports the balance of conservation, reconciliation, biodiversity, and climate action.

Uplands is a Canadian National Historic Site. In 2019, the Minister of Environment and Climate Change designated Uplands – including Uplands Park and its surrounding residential landscape and architecture – as a National Historic Site, with a federal investment to support the recovery of at-risk plant species unique to the area. This designation recognizes its ecological and cultural significance and highlights the need for place-based environmental leadership.

Oak Bay contains six (6) of the CRD’s 10 globally significant Key Biodiversity Areas, including Uplands Park. These sites depend on the surrounding Garry oak urban forest as a protective buffer that maintains habitat integrity.

Loss of mature Garry oaks has already caused species extirpations. The Western Bluebird disappeared from Vancouver Island in 1995 due to losses of habitat and mature Garry oak woodlands. Restoration programs are now attempting to re-establish populations, and Uplands Park is a key site because of its connectivity to Haro Strait regional migration routes.

Uplands park and neighbourhood form the ecological lungs of Oak Bay. With around 45% canopy cover – one of the highest in the region – this area provides essential ecosystem services. Removing roughly 30 mature native trees would create a long-term gap that is irreplaceable within human timescales; Garry oaks can take more than 150–200 years to reach full maturity.

Uplands Park-Cattle Point support the highest concentration of rare species in Canada.The surrounding neighbourhood provides wildlife corridors that link habitat north to Saanich and south to the Government House woodlands and MEEQAN (Beacon Hill Park).This positions the Uplands as a model for ecosystem-based planning, Indigenous partnership,and climate-focused innovation.

Natural assets provide millions of dollars in community services. Urban forests provide cooling, stormwater absorption, drought protection, clean air, wildlife habitat, mental and physical health, and carbon sequestration services. National standards for accounting for ecosystem services (CSA Group, 2023) make clear that such assets must be integrated into land-use decisions.

Uplands is a significant part of network of Garry Oak ecosystems that occur only in a narrow zone along the Salish Sea and are the most at-risk ecosystems in BC. Less than 5% of Garry oak ecosystems remain relative to their extent in 1900, and only about 1% of this ecological zone is undisturbed today.

Native plantings are necessary on this environmentally sensitive site. On land near Uplands Park, Landscape Plans should include at least 70% native species—such as Garry oak, Arbutus, ocean spray, camas, and native grasses—to maintain habitat value. Heavy reliance on non-native ornamentals (Yoshino Cherry), shrubs (Hicksii yew), and grasses (Hakone grass) diminishes biodiversity and undermines the National Historic Site’s ecological resilience.

Climate commitments require biodiversity protection. Oak Bay, the CRD, BC, and Canada have all adopted climate adaptation and mitigation goals aligned with the IPCC, emphasizing the importance of relational approaches to land and water stewardship, which include conserving and restoring native ecosystems such as Garry oak habitats.

https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/downloads/outreach/IPCC_AR6_WGII_FactSheet_Biodiversity.pdf

As presented, the proposal offers limited community benefit – six high-end units – while imposing substantial and irreversible impacts on the broader landscape. We encourage an approach that places long-term environmental stewardship above short-term intensification, ensuring that Oak Bay continues to protect the rare and declining ecosystems that define its character and support community well-being.

For these reasons, we urge decision-makers to prioritize long-term ecological stewardship and cultural responsibility over short-term intensification, and to ensure that development on this site aligns with the unique natural and cultural heritage of Uplands.

The community petition opposing the development continues to grow with nearly 500 signatures. https://lansdowne.lovable.app/

Upcoming Council Decision Oak Bay Council will vote on the proposal at the meeting scheduled for:Monday, November 24, 2025 – 7:00 PM Residents wishing to provide input can email Council at – obcouncil@oakbay.ca

Update: The proposal was declined as presented.